Voice Leading

Leading Notes

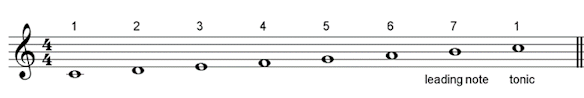

The behaviour of the leading note is crucial to writing good harmony, and good compositions. The 7th degree of the scale is called the “leading note” because it has a strong tendency to rise by a semitone step to the tonic – it leads to the tonic.

This movement happens in the progressions V-I, and vii°-I. Chord vii° works in the same way as chord V, so in this lesson I will just talk about chord V. Most of the examples are in the melody part, but the same guidelines apply if the leading note is the bass.

In other progressions, the leading note can move in other ways, but in the progression V-I, it normally moves in the expected way, up by a semitone step to the tonic note. The important thing to grasp about this rule when you’re writing music, is that the leading note movement to the tonic happens when the harmony changes from V to I. It does not mean that the leading note is only ever allowed to move to the tonic and not to any other note.

The change from the leading note to the tonic in V-I is called a “resolution”. The resolution happens at the moment that the chord I and tonic note sound.

Often, the tonic follows immediately after the leading note. But sometimes the resolution isn’t immediate, and sometimes a leading note doesn’t need a resolution at all. This can cause some confusion, so let’s dig a bit deeper.

The behaviour of the leading note depends on where the chords are changing in the music, which chords are being used, and also the function of the leading note: is it an accented chord note, or a less important decoration note?

Let’s look at some examples of how leading notes behave.

- The leading note rule only applies when the harmony is V-I. If the harmony is, for example, iii-iv or V-vi, then these rules don’t apply, (but rising to the tonic still might be a good solution in some situations).

- When the leading note is an accented chord note in chord V, it must normally rise by step to the tonic. Don’t forget that even in an unaccompanied melody, there is normally an implied chord progression supporting the whole melody.

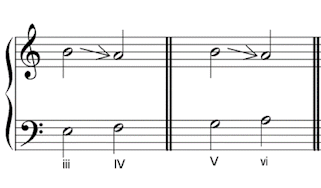

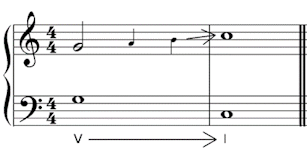

- If there is decoration following the accented leading note, this does not change the fact that the leading note needs to resolve to the tonic, but the resolution will not be immediately after the leading note. Here for example, the B is a chord note, and the A and G are decoration notes (I’ve made them smaller to show that they are less important, but they would be written normal size usually, of course). The B still needs to rise to C.

- An exception to this rule is if the leading moves by step for four or more notes in a row, then it may move elsewhere other than the tonic. This is because the stepwise pattern in the scale leads the melody to a different note rather than the tonic. This only works with steps.

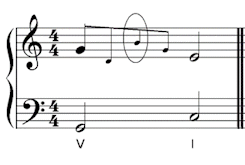

- When the leading note is an unaccented decoration note it should still move up by step to the tonic if it occurs at the same time the harmony changes. Here for example the accented chord note in chord V is G, and the A and B are decoration notes. We should use a tonic note C, rather than G or E, because the leading note moves at the same time that the chord changes.

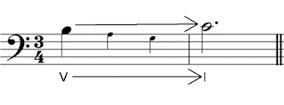

If the leading note is a decoration note and it does not occur at the point where the harmony changes, then there is no obligation for it to rise. But again, often it will still be the best solution. Here, the accented chord note is G, and D, B and G are decoration notes. The last note before the chord change is G, not B, so we don’t have to move to the tonic.

To summarise: the leading note rises to the tonic in V-I

- At the places where the chords change and/or

- At the places where the melody moves into chord I

- If you are unsure about where a leading note needs to move to, the safest option will be to let it rise to the tonic.

7ths

We’ll now look at the normal voice leading behaviour of the 7th in an added 7th chord, in a single line of melody. The same advice applies whether it is a melody part, inner part, or a bass part.

Added 7ths normally resolve downwards by step when the harmony changes. For example, the 7th in V7 is expected to fall to the mediant, when the harmony moves to the tonic.

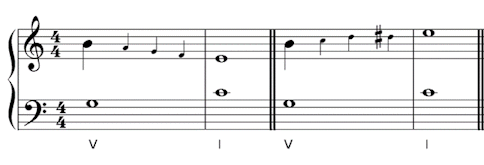

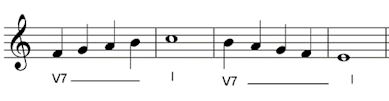

In (1) here, the 7th in V7 (F) falls to the mediant (E). In (2) it does not fall, and the melody is less satisfactory, because the F does not move smoothly.

If the melody uses both the leading note and 7th of V7, it is usually the note which is nearest to the chord change which decides the voice leading.

Here, the melody during the V7 chord includes both the notes F, the added 7th, and B the leading note. When the B is the closest to the chord change, it resolves upwards to C. In the next bar, the added 7th F is the closest to the chord change, so it resolves downwards to E.

If you use two 7ths in different registers, both will need to resolve, which can make it very difficult to continue in a satisfactory way. It is better to avoid using two 7ths for this reason.

A better solution here would be to start on G: