Dissonant Melodic Intervals

Augmented and diminished melodic intervals are uncommon but do sometimes occur. Dissonances should resolve by step: move from the dissonance to the nearest possible note. In most cases this will mean a semitone step.

Augmented 4ths/Diminished 5ths (The “Tritone”)

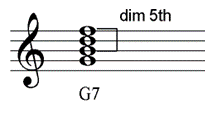

In a dominant 7th chord, two of the chord notes make a diminished 5th. For example, in G7, the notes B-F are a diminished 5th. Turned around the other way, F-B makes an augmented 4th. The term “tritone” refers to either interval.

This interval can occur melodically, if the two chord notes are used in succession.

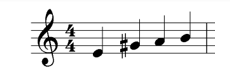

For example, here, the V7 chord in A minor (E7) includes the notes E-G#-B-D, with G#-D making an augmented 4th. The augmented interval sounds fine here, as it is simply part of the chord.

Augmented 4th/diminished 5th intervals also occur when chord IV moves to chord V, if the subdominant note moves to the leading note.

In this D minor example, the subdominant G moves to leading note C# (augmented 4th) in the top part.

Placing the augmented 4th into the melodic decoration softens its harshness a little.

Diminished 4th/Augmented 5th

When i (minor tonic) is followed by V, the mediant in the tonic chord can fall to the leading note in V, creating a diminished 4th. In the key of D minor for example, the notes would be F-C#.

Here, in the top part, the first chord note D is decorated with E (passing note) and F (auxiliary harmony note).

The F then falls by a diminished 4th to C# (leading note in V). Notice that the C# moves by step to D.

In this case the dissonance is again softened because it occurs as part of the melodic decoration. However, you can also occasionally find this interval occurring within the main harmonic outline too, with quite a dramatic effect. (Use it very sparingly!)

Choosing from the Melodic Minor Scales

The melodic minor scale has a raised 6th and 7th degree on the way up, but not on the way down. This means it can sometimes be confusing whether you should be raising a note by a semitone or not when writing music in a minor key.

There is a certain amount of artistic licence here – sometimes either version of the scale can be used. But in some situations there is only one right answer. You should use your knowledge of theory to guide you in your choice. It is certainly not the case that the ascending version of the scale should only be used where the melody ascends, for example.

The correct choice of notes depends on two things: the implied harmony, and the avoidance of augmented 2nds.

The following examples are all in A minor.

1. 7th degree to tonic: raise the 7th. The leading note gets its name from the fact that it has a strong pull towards the tonic. In almost all cases where the leading note is moving to the tonic, (ascending pattern), raise the 7th.

2. 7th degree auxiliary: raise the 7th. When the tonic note is decorated with a lower auxiliary note, the 7th should be raised. This is the same leading note function described in 1.

3. 6th and 7th degrees to tonic: raise both. When the leading note has been raised, the 6th also needs to be raised to avoid the augmented 2nd between the 6th and 7th degrees of the scale.

4. Dominant decoration: raise 6th/7th. In point 3 above, the melody notes would fit with a dominant E major chord. When the harmony is chord V, the decoration should agree with the chord notes. So, if you use a descending scale pattern, the 6th and 7th are still normally raised.

5. Subdominant decoration: do not raise 6th/7th. Minor chord iv includes the unraised 6th degree of the scale (e.g. F in a D minor chord (iv) in the key of A minor). Decorate chord iv with the notes that agree with the chord.